The Impacts of Ukrainian Invasion on China Part I - Soviet on the Outside, Qing on the Inside

With the recent invasion of Ukraine undertaken by Russia, one spot of foreign policy challenges that the world needs to still wake up to is China. There are a large number of reasons why Russia has significance for China, and it is not merely about economy or increasing global isolation.

Soviet Union, modern Russia's precursor, was an ideological inspiration and mentor of the Chinese Communist Party till the death of Joseph Stalin, following which they parted ways. Of course, even after the Soviet collapse, there continues to be interest in Russian affairs in a variety of ways.

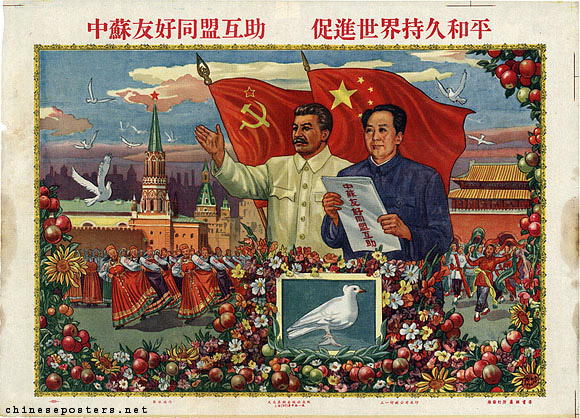

|

A 1949 Poster Hailing the Sino-Soviet Peace and Friendship Treaty. The Putonghua reads as follows: "The Sino-Soviet Alliance for Friendship and Mutual Assistance promotes enduring world peace" |

This is the first part of a multi-part series as to why the latest Russian - Ukrainian challenge carries multiple implications for China.

PART I - SOVIET ON THE OUTSIDE, QING ON THE INSIDE – MAKING SENSE OF THE CHINESE PROPAGANDA

Global Times, the mouthpiece on international affairs of the Chinese Communist Party, interestingly has been one of the few papers to have highlighted the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union. It conducted an interview with an expert scholar, Zheng Yongnian of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen campus, to understand the lessons for ‘today’s China’; however, it became an opportunity to compare the US’ current state with the Soviet Union.

The Lesson Internalized in the Chinese System

What is fascinating is the emphasis on deriving the

right lessons from the collapse of the Soviet Union. One of the key lessons

over the decades has been the need to provide economic growth and good government. The failure to change and adapt to the modern times

that Zheng has highlighted in this interview does not seem very different from

the standard party line in fact. Contrast these two statements, one from a 2013

Diplomat article quoting Li Jingjie, a Soviet expert at the Chinese Academy of

Social Sciences, and the other from the interview:

“It was the CPSU (Communist Party

of the Soviet Union) that collapsed first. CPSU leaders did not

understand economics and they steadfastly avoided reform because they

dogmatically believed in their model. The CPSU never renewed

itself and did not adapt with the times… In seventy-plus years, there was

no development of democratic politics. Once they began, under Gorbachev,

they were too late and the reform strategy was erroneous – which was the

precipitating cause of the collapse.”

Li Jingjie

“It should be noted that the Russian civilization and

model does not necessarily lead to failure. Many reasons have been summarized

these years for the dissolution of Soviet Union in terms of politics, economy

and the influence by the West, but in my opinion, the fundamental reason is

the Soviet Union's inability to keep up with the times.”

Zheng Yongian

What is interesting however is the subsequent lessons

that have been drawn from it. If one were to go by the interview, Zheng

essentially advocates for a relative degree of openness towards the outside

world, albeit economic in nature, as essential to the survival of the Communist

set up in China. This is where till the advent of Xi Jinping, there was a

semblance towards openness. To that end, the party high rankers and

intellectuals in China were keen in the idea of some form of openness and

transparency even as early as the Gorbachev era of the late nineteen-eightees, as scholars have

argued. This however translated not into democratic thinking as one would have

expected, but into greater sensitivity towards public opinion.

The economic openness argument continues to stay

strong however, even if couched in terms of a big market that offers ample

opportunities. This talk about as strong middle class is an acknowledgment

without saying the obvious - the roots of the level of economic prosperity that

China has achieved because of being part of the global supply hub; however, it

also is perhaps a reflection of the fear of falling out of the supply chain

without being able to make that transition that it wants to make - a far more important role for “domestic

circulation” and self-sufficiency, and future economic growth to be driven by,

domestic consumption rather than exports.

China – a Civilizational

Competitor or Not?

While comparing the Soviet Union’s fundamental

structure with that of Tsarist Russia is perhaps not entirely wrong, it is

interesting to note that the interview posits Russia as a civilizational

competitor, and not China. This is in many ways a departure from stated party

position. Chinese Communist Party, particularly in the Xi Jinping, has more

often than not talked of the alternative that China offers, which wrapped in

the civilizational robes, clearly alludes in the same direction.

As Alison Kaufman has pointed out in her 2018 piece, the shift in China’s global status allows Xi

to reevaluate traditional Chinese civilization in relation to Western

civilization, and in relation to China’s own socialist aspirations. As per

Kaufman, the concept of a “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is a kind of

signaling, an assertion that the Chinese civilization has presented to the

world – a successful alternative to the west which stems from its

civilizational past. In this view, the CCP is a natural successor to that past,

and this CCP led China can create a “community of common destiny”, with China

in the leadership.

This too is a message that seeps

through the party despite its internal differences. For instance, when one

hears Wang Yi, the foreign minister of China, talk about China’s

endeavor “to foster a new form of international relations and build a community

with a shared future for mankind”, the fog of vagueness in the message gets

cleared by the actions on the ground, particularly the rhetoric it engages in

with respect to ‘Western values’. This

is a core belief of the Communist Party of China – as Wang

Tingyou’s write up in the “Red Flag Manuscript” journal of the

party states, the ‘common values’ espoused by the party need not be the same as

the ‘universal values’ espoused by the west. To this end, Wang’s following

remarks epitomize much of the consensus on thinking in the party:

"Common value" has

nothing in common with the so-called "universal value" in the West.

All consensus values, including the common value of all mankind, are based on

the recognition of each other’s special values. Therefore, they are all

relative, developing, and changing. They will change with changes in

conditions, scope, and time, not absolute, permanent, eternal, and immutable…

For

another example, peace has always been the common aspiration of mankind. In the

eyes of some people, this is a "universal value." Reality tells us

that in a world where there are class antagonisms, conflicts of interest, and

hegemonism, this kind aspiration simply cannot be realized, since violence and

war are still the fundamental means by which Western hegemony forces defend

their own interests and plunder the people of other countries.”

References to Qing China – an

Internal Criticism?

What perhaps gains the most

attention is the reference to Qing dynasty China in the interview, and an

attempt to create an analogy with modern day United States. It is a distinctly

cultural reference that many would fail to understand, simply because the

memory of the Qing era China is a stark one in the popular culture to this day.

Ming era China and Tang Era are seen as the aspirations, while Qing perhaps

remains best ingrained as one of weakness and disaster despite it being a part

of only the last few decades of a centuries old system.

A great example of this memory

remains in the expat Chinese settling in South-east Asia under British rule as

labourers forming secret societies, many of which sought to overthrow the Qing

dynasty. Never mind that the Qing had created the modern China’s boundaries now

claimed by the CCP; the aspiration is to pander to the largest ethnic group of

Hans who still carry remnants of the anti-Manchu sentiment birthed during the

late Qing period. The

ultimate aim to ‘oppose Qing and restore Ming’ (fanqing fuming 反清复明) i.e. to overthrow a backward

system to build a new one in order to

prevent China from being colonized by foreigners was one

fitting into the Communist ideology, for it talks about colonization and

perpetuates a memory of ‘humiliation’ of the Chinese people by outsiders.

The use of the analogy of the

misguided elite however to criticize the Americans seems to reveal more than

what meets the eye. Is there some kind of warning to the elite of the Chinese

Communist Party to toe the official line? Given the lessons that the Soviet

experience has to offer in the official Chinese memory, the aim might have very

well been at those camps opposed to the Xi faction, many of whom in the past

were following a gradual path of opening up as was

seen in the case of former premier Wen Jiabao. The particular reference

to Qing dynasty also talks about ‘outsiders’ being the reasons for oppression. Given

Xi’s antecedents as an out and out princeling who see access to power

as a natural right, is this an indication also on the populist

factions who come from families of less privilege, as is

the case with his premier Li Keqiang? After all, Li

Keqiang continually takes a strong contrarian position on the economy.

Prosperity being the bedrock on which Xi bases his right to rule, any challenge

would be seen as a crossing of the line. With Xi now

giving himself the highest authority in the political order of China

to become the third of a pantheon containing Mao Tse Tung and Deng Xiaoping,

any deviation would henceforth become intolerable, much in the fashion of

typical courtroom politics.

What is in the near future is a

guess in all likelihood; however, there are some patterns in this interview

that reflect the broader changes happening within China and its mindset. One

thing is certain – Xi’s China is determined to not be the next Soviet Union.

Comments